Return to Study Guide: How to Study the Bible, by Jeffrey Bruce and Brian D. Asbill

Download PDF (5 pages)

Module 2: Worldviews and the Battle for Meaning

by Jeffrey Bruce and Brian D. Asbill

I. Before we can even begin to understand correct methods of interpretation, we must reflect on some philosophical issues. This is because every time we come to read a text, we carry a number of presuppositions that in some sense determine what we will get from the text. We thus must discover what some of these presuppositions are, and

II. whether or not they are beneficial in the hermeneutical enterprise. A brief history lesson will help facilitate this.The Battle for Meaning in History.

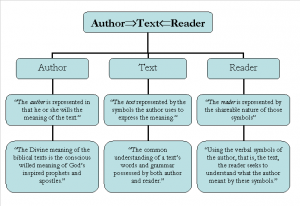

A. This chart illustrates the battle for meaning in interpretive history:[1] [1] Ibid., Hermeneutics, 8. [NOTE: Graph is a PDF download.]

SEE GRAPH

B. As we see, there has been a radical shift in the locus (or place) of meaning over the course of history. Whereas meaning once resided in the author, it has come to reside in the reader! But what position is correct? Who actually determines what the text means? Is the meaning of the text something the author intended? Is the meaning somehow residing in the text? Are we the readers, responsible for inventing or creating whatever meaning meets the needs of our communities? All three of these views must be carefully examined and critiqued.

1. The Text – As mentioned earlier, this view was popular at the turn of the 20th century. Here are some of the problems inherent in this view of where meaning resides.

a. This view understands language as an actor (i.e. something that sets things in motion) rather than a label one attaches to passive objects. However, the text is only a collection of letters and symbols, while meaning the product of man’s reasoning and thoughts.

b. As Stein says, “While a text can convey meaning, it cannot produce meaning.”

c. The text is an instrument to covey meaning. Without an author, the text loses intent, and fails to convey meaning.

2. The Reader – In our Postmodern world, this view of meaning is generally preferred. However, this position also has a number of conspicuous problems.

a. Klein, Blomberg and Hubbard note that, “the main weaknesses of reader-response criticism lie in its relativism.” For example, if the meaning is nothing more than something agreed upon by the readers (perhaps because of interpretive conventions), than proponents of this view should never object to interpretations contrary to their own!

b. Further, if they ever want to communicate anything (even their own view of meaning), they must assume common interpretive conventions of interpretation. However, this is precisely what they cannot assume, and thus their argument is self-defeating.

c. Another problem is that this view cannot account for how texts transform readers, generating interpretations and behaviors that cut against the grain of preunderstandings, presuppositions, and social conditioning.

d. While this view might help us not put too much stock in our own interpretive faculties, it ultimately falls short in explaining meaning.

3. The Author – The notion that meaning resides in the author seems to be the most natural (not to mention most courteous) way of understanding meaning. There are several reasons for this:

a. This view seems most natural to us experientially, for we tend to think of meaning as something the author intends.

b. When we say something, we tend to think that we are the ones giving it the meaning, and not the listener, or the thing spoken.

c. There is biblical precedent for this view of meaning (1 Cor 5:9-11; 1 Pet 1:10-11; 2 Pet 1:20; 2 Pet 3:16).

d. “We cannot even argue against this view without at the same time agreeing with it, for we must seek to understand what writers mean by their words in order to engage in discussion with them.”

III. Lessons to Learn and Definitions to Remember

A. Since we have established that meaning resides in the author, it is important to define some terms a little more accurately.

1. Meaning – What an author intends to communicate through the text.

2. Implication – “those meanings in a text of which the author was unaware but nevertheless legitimately fall within the pattern of meaning he willed.”

3. Significance – “refers to how a reader responds to the meaning of a text.”

B. The relationship between these concepts (as well as the relationship between the author, text, and reader) are illustrated in the chart below:

SEE GRAPH [NOTE: Graph is a PDF download.]

C. The author thus communicates a message, which has a certain range of implications delimited by his or her intent. The reader seeks to understand the significance (or applications) that stem from this fixed meaning.

D. While some of this might seem fairly straightforward, it is interesting how often the church has failed to understand some o f the things we have learned, as the next case example will show.

|

Case Example #2: Romans 7:7-25 [1] Since Augustine this passage has been interpreted as referring to the believer’s internal struggle with sin. However, many in the early church (e.g. John Chrysostom) interpreted this as the struggle of the faithful Jew under the New Covenant. What explains this shift in interpretation? The answer is quite straightforward. As Jews comprised a less and less integral part of the church (and consequently, as anti-Semitism began to spread in the church), this passage must have lost relevance. Thus the church saw the believer view as a more relevant and promising interpretation. However, in doing this they developed a meaning for the text which seems quite foreign to the context of the passage. For example observe the following issues:

Having gone through these questions, it seems relatively clear that the struggle Paul is referring to here is that of a believing Jew under the Old Covenant, and not a believer. Perhaps the church is indeed guilty of conjuring up a meaning in this text that was never truly there! [1] For a more in depth presentation of the material presented in this case study, see Walt Russell, “Insights from Postmodernism’s Emphasis on Interpretive Communities in the Interpretation of Romans 7,” JETS 34 (December 1994) 511-527. |

Return to Study Guide: How to Study the Bible, by Jeffrey Bruce and Brian D. Asbill

FOR MORE:

Every time we come to read a text, we carry a number of presuppositions that in some sense determine what we will get from the text. We thus must discover what some of these presuppositions are.

_____________

Being wise in a very unwise world during these End Times

“Only 6% of Christians

now hold to a biblical worldview

according to Barna,

while 88% of Christians

borrow from contradictory worldviews

for their beliefs.”

– Jan Markell: I Never Thought I Would See the Day

May 26, 2021

Is Jesus’ Worldview – your worldview

Consider these biblical views: Voting Dichotomously, What Jesus Stands For, What Jesus Taught, Which Jesus Do You Serve?, Following, Following Someone, Exposing a dichotomous heart, One Thing You Lack, Reconsider Your Life, A God Damn,

If your heart follows to the beat of

a different drum

than what the band of Jesus marches to;

if how you see the world

is not how Jesus see’s the world;

if you are FOR

what Jesus is AGAINST…

where is your belief in Jesus?

34 Ethical Issues All Christians Should Know | from Crossway | from Wayne Grudem’s Christian Ethics: An Introduction to Biblical Moral Reasoning

Be Berean (site search)