Return to Study Guide: How to Study the Bible, by Jeffrey Bruce and Brian D. Asbill

Download PDF (5 pages)

Module 3: Context, Context, Context!

I. Having looked at our own presuppositions toward the text, we can now look at the Bible itself, both from a historical standpoint and a literary standpoint. This will help us to bridge some of those “gaps” mentioned earlier, and it should make us aware of some faulty interpretive habits.

II. The Historical Context

A. Not only did the Biblical writers live a long time ago, but operated in a world quite foreign to us. Their cultural values (for better or for worse) are not ours, and are at times strikingly different.[1] The following chart is exemplary in showing the differences that exist between our culture and Eastern culture (which is quite similar to the culture of the Bible).

East-West Cultural Differences

Presented by Tran Van Mai, Ph.D.

Second Annual Indochinese

Conference CSUF – Fall 1981

| EAST | WEST |

| BEHAVIOR: | BEHAVIOR: |

| We live in time | You live in space |

| We are always at rest | You are always on the move |

| We are passive | You are aggressive |

| We like to contemplate | You like to act |

| MIND SET: | MIND SET: |

| We accept the world as it is | You try to change it according to your blueprint |

| We live in peace with nature | You try to impose your will on her |

| Religion is our first love | Science is your passion |

| We delight to think about the meaning of life | You delight in physics |

| We live in freedom of silence | You believe in freedom of speech |

| We lapse into meditation | You strive for articulation |

| LOVE: | LOVE: |

| We marry first, then we love | You love first then marry |

| Our marriage is the beginning of a love affair | Your marriage is the happy end of a romance |

| It is an indissoluble bond | It is a contract |

| Our love is mute | Your love is vocal |

| We try to conceal it from the world | You delight in showing it to others |

| LIFE-STYLE: | LIFE-STYLE: |

| Self-abnegation | Self-assertiveness is the key to your success |

| We are taught from the cradle to want less and less | You are urged everyday to want more and more |

| We glorify austerity and reconciliation | You emphasize gracious living and enjoyment |

| Poverty is to us a badge of spiritual elevation | It is to you a sign of degradation |

| In the sunset years of our life, we renounce the world and prepare for the hereafter | You retire to enjoy the fruits of your labor |

B. In addition to these rather substantial differences, there are countless cultural peculiarities that must be taken into account in interpretation (e.g. finer points of Jewish law and custom, geography, monetary units etc.)

C. Thus an awareness of historical context is essential if one wishes to understand the message conveyed. As Osborne notes: “Since Christianity is a historical religion, the interpreter must recognize that an understanding of the history and culture within which the passage was produced is an indispensable tool for uncovering the meaning of that passage.”[2]

|

Case Example #3: Revelation 3:14-22 As we all know, this text has historically been used in evangelistic invitations. Indeed, who has not heard someone say some thing to this effect; “Jesus is knocking on the door of your heart, asking if he can come in.” Furthermore, who hasn’t heard verses 15-16 used in an exhortation to avoid being “lukewarm” in one’s attitude toward Jesus? However, the cultural context points decidedly against both of these interpretations. Consider the following:[3] · The church is being addressed here. Specifically, the church of Laodicea. · Laodicea was the wealthiest city in Phrygia, due in part to the production of a black glossy wool. · The city was famous for its medical school, whose students followed Herophilos, a man famous for creating heterogeneous mixtures such as spice nard for the ears and an eye-salve known as “Phrygian Powder.” · Laodicea lacked a convenient water supply, and by the time the water reached the city, it was tepid. This was in contrast to cold, pure waters of Colosse, 11 miles east, and the therapeutically hot waters of Hierapolis six miles north. How do these cultural insights effect the common interpretation of verses 15-16? How do they effect the common interpretation of verse 20? It appears that they affect them a great deal. Christ is not addressing attitude, and he is not knocking on the door of the believer’s heart, but on the door of the church. Furthermore, the rest of the context (e.g. 16-19) begins to make a lot more sense in light of the cultural background. What a difference some historical context makes! |

III: The Literary Context

A. The church has historically held to the clarity (or perspicuity) of scripture. This doctrine states that the message God conveys to mankind is comprehensible to us. Thus, “The Bible’s meaning can be understood when read in its literary, linguistic, and historical context in mind.”[4] In virtue of these considerations, literary context becomes even more important, because it actually helps us in understanding God’s word.

B. Literary context is what most people think of when they think of context. As Fee and Stuart say, “literary context means that words only have meaning in sentences, and for the most part biblical sentences only have meaning in relation to preceding and succeeding sentences.”[5] Further, Osborne notes that this is, “the most basic factor in interpretation.”[6] All of this may seem very commonsensical (i.e. that context is determinative in understanding authorial intent), but it is nonetheless important that we draw a few principles from this.

1. Find the generic conception. Passages tend to have an intrinsic genre (i.e. a generic conception). This “mini-genre” is the sense of the whole by which the interpreter can determine what any part means.[7] When reading a passage (e.g. Romans 8:1-11), try to figure out what the dominant idea is. This generic conception should make the best sense out of all the constituent parts in the passage. In doing this,

one guards against the atomistic tendency to read too much into to a smaller unit of scripture.

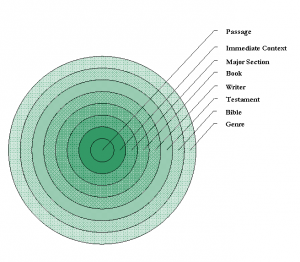

2. Read from the “top down.” As Russell notes, “meaning comes from the top down, not from the bottom up, from the larger units of scripture to the smaller units.”[8] Osborne provides the following chart that is helpful in understanding this principle:[9] SEE GRAPH

This diagram shows the limits of the interpretive process. We start with the Bible, and then move closer toward the text under consideration. As we move close to the middle, the influence a give circle has upon the meaning of the passage increases. Thus, when we get to the text itself, it makes sense within the various literary contexts that it falls under.

IV. Having learned these important lessons on literary context, it is important to see how we can apply them to our study of the Bible.

|

Case Example #4: metanoia (metanoia)

Early in the 20th century, famed theologian and founder of Dallas Theological Seminary Lewis Sperry Chafer argued that the Biblical idea of repentance did not entail a change in lifestyle or remorse for sins committed. What was his reasoning for this conclusion? The Greek word for repentance (metanoia) simply means “change” (meta) of “mind” (noia). Repentance was thus nothing more than a cognitive change, and did not (in the meaning of the word) relate to a changed lifestyle or remorse for sins. Besides the fact that this is what is known as a “semantic fallacy” (specifically, the Root Meaning Fallacy), it is also an excellent example of reading from the “bottom up,” rather than the “top down.” Chafer is basing his interpretation of repentance from the roots used in the word, and not from the ways the word “repentance” is used throughout the Bible. If he were to do this, it would become obvious that in no way does repentance only refer to a “change of mind”! Chafer’s atomism has caused him to make a major interpretive error; one that he would have avoided if he had read from the “top down,” and had tried to look for the “generic conception” in passages dealing with repentance. |

[1] For a good overview of 1st Palestinian cultural values, see Bruce Molina, The New Testament World 3rd. ed (Louisville: WJK, 2004).

[2] Grant Osborne, The Hermeneutical Spiral: A Comprehensive to Biblical Interpretation (Downer’s Grove, Ill: IVP, 1991) 127.

[3] The following information is taken from Robert Mounce, The Book of Revelation, rev. ed. (NICNT: Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998) 107.

[4] Fred Maybe, TTBE 517 Hermeneutics and Bible Study Methods (Coursepack), 4.

[5] Ibid., How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth, 23.

[6] Ibid., The Hermeneutical Spiral, 21.

[7] Ibid., Hermeneutics TTBE 517, 16.

[8] Ibid., Playing with Fire, 65.

[9] Ibid., The Hermeneutical Spiral, 21-22.

Return to Study Guide: How to Study the Bible, by Jeffrey Bruce and Brian D. Asbill